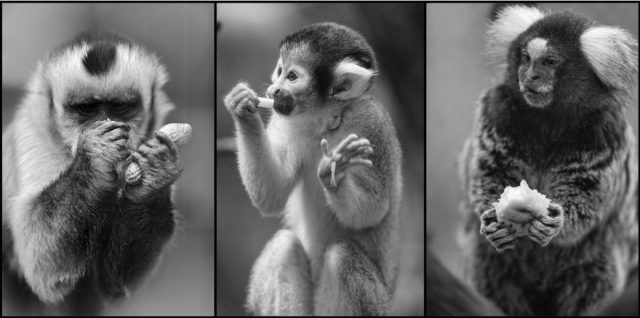

Humboldt’s squirrel monkey gets fooled by the “French Drop” magic trick. Credit: E. Garcia-Pelegrin et al. , 2023

The key to a successful magic sleight-of-hand trick is how well the magician manipulates the audience’s perception, especially hand movements, as this is critical to how they anticipate the actions of others. To find out more about how humans might deal with such a misdirection, researchers in the UK performed simple magic tricks on three species of monkeys to see if they could be fooled. They found that those species with at least partially opposing thumbs were deceived, suggesting that having similar anatomy (and thus biomechanical ability) plays a vital role in the illusion. They describe their results in new leaf Published in Current Biology.

“Magicians use sophisticated techniques to mislead the observer into experiencing the impossible,” said co-author Elias García-Pellegrin, who practices magic and conducted this research while completing his PhD at the University of Cambridge. “It’s a great way to study blind spots in attention and cognition. By investigating how primate species experience magic, we can understand more about the evolutionary roots of the cognitive deficiencies that leave us vulnerable to magicians’ craftiness. In this case, whether having the manual ability to produce an action What, like holding an item between your finger and thumb, is necessary to predict the effects of that action on others.”

The researchers focused on three species with different hand anatomy and associated biomechanical capabilities: yellow-breasted capuchin monkeys, Humboldt’s squirrel monkeys, and common monkey. For example, capuchins are known for their manual dexterity, due in part to the fact that they can individually control their fingers. So they can perform a scissor grip (holding an object between the sides of two fingers), as well as a fine grip (bringing the thumb to the index or middle finger). They can even probe, pinch, or grip something with both hands, like humans, and use stone tools to crack nuts.

Squirrel monkeys aren’t nearly as dexterous by comparison, but they have been known to use simple tools on occasion. They have hinge-like joints that limit the rotation of the thumb, so the thumb cannot be fully resisted. But they can still touch the index side of the middle finger (but not the pads). Marmosets, on the other hand, evolved for vertical movement such as climbing tree trunks, and opposite thumbs wouldn’t be an advantage for that, so they don’t have it. They have rigid thumbs instead. According to the authors, orangutans climb by spreading their five digits as wide as possible to increase surface area, and bending all of their digits simultaneously to dig with their claws. They use a combination of force handles and scissor handles to manipulate objects.

E. Garcia-Pellegrin et al., 2023

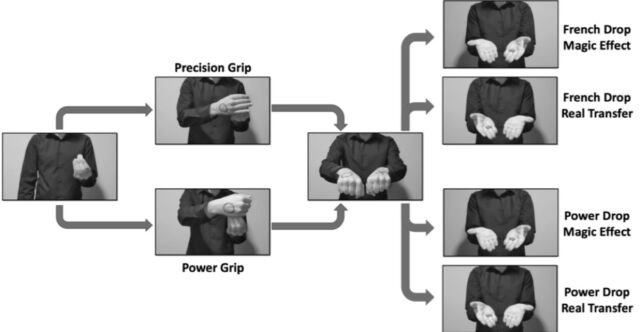

The researchers decided to use one of the simplest sleight-of-hand tricks in The Magician’s Handbook for their experiments: the “French drop.” This is when the magician holds a coin in one hand, then reaches out with the other hand and grabs it with the palm facing inward, thus hiding the coin behind the fingers. The idea is to get the audience to focus on a second hand and assume the coin has been moved. But when the magician opens the second hand, it is empty – because the magician had dropped the coin into the original palm. The ability to block the thumb is key to the magic trick, so the thumb must be able to block.

Garcia-Pelegrain and his colleagues replaced the coin with bits of food: peanuts for the capuchins, dried mealworms for the squirrel monkeys, and marshmallows for the monkey monkeys. One version of the experiment involved performing the French drop on all of the monkeys to see which ones had been duped. They also conducted a control experiment where food vaccines were actually transferred from one hand to the other. Finally, the team performed a third version of the experiment using a modified magic trick they called the “Power Drop,” using the full fist—a hand movement that can be performed by all three species of monkey. If the monkeys correctly guess which hand is holding the morsel, they can eat the morsel as a reward.

The Capuchins were fooled, predictably, by both French tricks and modified Power Drop tricks. They chose the wrong hand in those trials about 81 percent of the time. But they chose correctly in direct transfer experiments. This pattern of choice has also been seen in humans [also] It is usually misled by the influence of the magical French projection, but not by its true transmission.

E. Garcia-Pellegrin et al., 2023

Squirrel monkeys, with their partially opposing thumbs, also fooled with the French drop trick, choosing the incorrect hand 93 percent of the time, the opposite of what the researchers expected. “Squirrel monkeys can’t control with perfect precision, but they’re still deluded,” Garcia Pellegrin said. “This suggests that a monkey doesn’t have to be an expert on movement in order to predict it, just roughly able to do so.”

But the monkey had the opposite pattern. They mostly chose correctly for the French drop effect, being fooled only 6 percent of the time, but chose incorrectly when the bite was passed to the other hand. This is evidence that they view sleight of hand differently from the other two species of monkeys, possibly because they lack opposable thumbs. “It appears that in this case, the apes were more likely to use heuristics to select the hand containing the reward initially regardless of the gestural act performed by the experimenter,” the authors write, a similar selection methodology used by corvids, which they do not have. Thumbs up at all.

According to the authors, their findings indicate that cognition—including the ability to predict the hand movements of others—is strongly influenced by inherent physical capabilities.

“There is growing evidence that the same parts of the nervous system that are used when we perform an action are also activated when we watch that action performed by others.” said co-author Nicola Clayton, a psychologist at the University of Cambridge. “This inversion in our neuromotor system may explain why the French drop works well with capuchins and squirrel monkeys but not with the monkey. It’s about the embodiment of knowledge. How a person moves their fingers and thumbs helps shape the way we think, and the assumptions we make about the world — plus what we might Others see it, remember it, and expect it, based on their own expectations.”

DOI: Current Biology, 2023.10.1016/j.cub.2023.03.023 (about DOIs).

“Twitteraholic. Total bacon fan. Explorer. Typical social media practitioner. Beer maven. Web aficionado.”