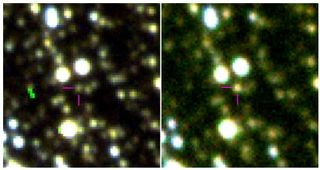

An exoplanet discovered by NASA’s Kepler space telescope, officially K2-2016-BLG-0005Lb. (Image credit: D. Specht et al, Kepler K2)

NASA’s Kepler space telescope has spotted a Jupiter-like planet in a new discovery, even though the instrument stopped working four years ago.

An international team of astrophysicists using NASA kepler space telescope extrasolar planet

“Kepler was also able to observe without interruption by weather or daylight, which allowed us to accurately determine the mass of the exoplanet and the distance of its orbit from host star Eamonn Kerns, an astronomer at the University of Manchester in the UK, He said in a statement

Related: Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)

The team is led by David Specht, Ph.D. A student at the University of Manchester, benefited from a phenomenon known as microgravity Einstein’s theory of relativity

Hoping to use the twisted light from a distant star to detect an exoplanet, the team used three months of Kepler’s observations across the sky where that planet is located.

“Seeing the impact at all would require a nearly perfect alignment between the foreground planetary system and the background star,” Kerns added in the same statement. “The probability of a background star being affected in this way by a planet is tens to hundreds of millions to one. But there are hundreds of millions of stars toward the center of our galaxy. So Kepler sat and watched them for three months.”

The team then worked with Ian MacDonald, another astronomer at the University of Manchester who developed a new search algorithm. Together we were able to reveal five candidates in the data, one of which clearly showed signs of an exoplanet. Other terrestrial observations of the same stretch of sky supported the same signals that Kepler saw of possible exoplanets.

“The difference in the vantage point between Kepler and observers here on Earth allowed us to triangulate where the planetary system is along our line of sight,” Kearns said.

Aside from the excitement of discovering an exoplanet with an instrument that is no longer even in service, the team’s work is notable because Kepler was not designed to discover exoplanets using this phenomenon. It is important to note, however, that in 2016, Kepler’s mission was extended. In 2013, after two reaction wheel failures, Kepler was proposed to be used on the K2 “Second Light” mission which would see the range discover potentially habitable exoplanets. This extension was approved in 2014 and the mission has been extended beyond the range’s expected completion date until it eventually runs out of fuel on October 30, 2018.

“Kepler was never designed to find planets that use the microlensing, so, in many ways, it’s surprising that it did,” Kerns said, adding that upcoming instruments like NASA’s Nancy Grace Space Telescope and ESA’s Euclid mission, could be Able to use the micro-lens to study exoplanets and will be able to do more of this research.

“On the other hand, Roman and Euclid will be improved for this kind of work,” Kerns said. “They will be able to complete the planet census that Kepler started.” “We will learn how the structure of our solar system is typical. The data will also allow us to test our ideas about how planets form. This is the beginning of an exciting new chapter in our search for other worlds.”

This discovery It was described in a study

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter Tweet embed . Follow us on Twitter Tweet embed And on Facebook.